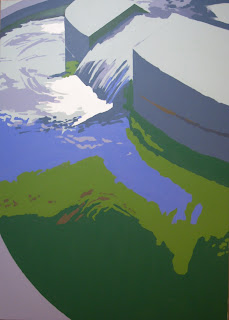

"Monument (Merrick Butte)", Oil on Panel, 8x8 inchesJerry Lebo, 2007

"Monument (Merrick Butte)", Oil on Panel, 8x8 inchesJerry Lebo, 2007Some of you are probably wondering what happened to me--having not posted to my blog for several weeks. No, I did not stop painting or have some terrible accident. Family is fine, thanks for asking. I am very much alive and kicking--but just decided to take a total break from my blog over the holidays--and then added a few more days for good measure. So I hope everyone had a good break, but it is now back to work and back to the studio!

The good news is that the holiday break gave me a chance to work through some issues in my own painting, as well as develop some new ideas and painting exercises. The painting exercises are thanks to my students, who continue to challenge me as I try to impart my ideas to them in new and innovative ways.

One of the questions that kept coming up for me during the holiday break was the rather basic question, "How does one learn to paint?" For a long time, I have heard from others who say that the only way to learn how to paint is to "do it". And, while this may be partly true, you can paint badly for a long time and not learn anything. My current students are quick learners and thirsty for new ideas on how to improve--so I have been challenged to come up with exercises to assist their process. Some of these have proven useful in my own work. And, I am now convinced, more that ever, that the key to improving is...are you ready...

learning to see.

No surprise, right? So what do I mean by “learning to see”? To put it simply, what I mean is increasing your ability to distinguish between colors, values, and their interactions—and use this knowledge in your art. To use a similar analogy from music (i.e., “learning to hear”), this would be the ability to hear the difference to between notes, pairs of notes (chords), and learn how they interact when played together—and to use that knowledge to make music.

Unfortunately, it appears there is a difference between music and art. That is, while everyone seems to take for granted that you need to practice for a long time before you go onstage—in painting people seem to think that you can write music the first day you pick up a brush. I mean everyone has two eyes, and it is simply copying what you see—isn’t it? Even artists have this bias in the back of their own minds--wondering why when they are not painting like a master after a decade or two. Would you expect to be able to write the equivalent of a Beethoven symphony after a decade of piano lessons—or, as most painters equivalently are doing, a decade or two of twiddling at the keys?

Okay, so how does one “learn to see” in practical terms. Let me give you an example. One thing that I have noticed about my students is that they are struggling translate what they see in their minds onto canvas. For example, it is very easy for me to say, "do you see that green…okay, mix the same color and value and put it on the canvas". But there are a lot of steps in the process. You need to be able to mix a color that is at least close to what you want (and in the right value), pick it up with the brush so that it is not too thin or thick, and make the right stroke on the canvas. There is a lot of room for error in this simple process.

Let me give you a more concrete example. One of the problems that my students have been struggling with is how to get the right "value" onto the canvas. Not the value they see in their mind, but the actual value required. What surprises me is that when I show them a value that is very dark--say slightly above black—they will mix and put something down one or two value steps lighter? Can’t they see? It is frustrating for them when this happens, and frustrating for me to watch. But, it reminds me of what Josef Albers says in "

Interaction of Color", where he says that even in his advanced painting class, only 40% of the students when shown two different colors could correctly pick the one that was darker than the other. And, these were his advanced students! So, it is not as easy as it sounds "to see".

Let me give you a more personal example. I tried an exercise the other day where I took a simple photograph that was in color and tried to guess how many equivalent grayscale values were in the photograph (one of the silly things I do in my free time). I guessed six. Then I printed the photo out as a black and white print--and I looked at it again—and could see there were in fact around eight. Then I did something I used to do as an exercise years ago, I went down in the studio and tried to match by direct comparison every tone in the picture by directly mixing the actual value (using ivory black and titanium white) and putting it down where I saw it on the printout. Guess what, I discovered by direct comparison that there were at least 10-12 values in the picture (although some were very close). This shows you how hard it is to see values in black and white photo—let alone color.

The funny thing was, after I did this exercise, I decided to start painting. And, guess what? My painting process felt a lot smoother, and I felt like I was in control of my values during the process. The exercise of simply looking for, and then actually mixing a set of subtle values, heightened my ability to see for hours after I did the exercise—maybe for longer.

So, there you go. This is what I mean by “learning to see”. Taking the time to do something that

physically forces you to struggle with seeing a value, color, or interaction between values or color. This is the best thing you can do for your painting—right now, today. Let me say that again in another way. If you want to be a better painter—don’t waste your time painting—do something that forces you to look harder and see something that you don’t normally see. The results will stay with you—and improve you work much more quickly than an hour spent painting badly.

Now, I know many of you won’t believe me—and will not take the time to do these types of simple seeing exercises. They are tedious—and not as fun as painting. But, believe me, this is what is needed to paint better. This is how you learn how to paint—challenge yourself to look and see—and you paintings will get better. It can work with composition, color, values, color interactions—all aspects of painting get better by physically doing an exercise that stretches you ability to see that thing you did not see before (not thinking or reading about it, but physically doing it).

Okay, so what exercises can you do? Of course, there are thousands. But, here is one exercise I know works—and you might want to do before you next painting session. Take a simple photograph, maybe of a still life or simple landscape—and print it out in black and white on an inkjet or laser printer. If you are working from photographs in the studio, you can use the same subject you are planning to paint. But, this is not a study you are doing, it is an exercise. You are

not trying to make something that you will use—it is something that you are going to throw away.

Start by putting some ivory black and white on the palette—and try to mix one of the values you see in the reference print—and then put it down right where you see it in the photo. You should compare the value before you commit to it. So, take a small dab of the mixture you have mixed on your palette and put it directly on the printout when you think it is. It will visually "disappear" on the printout if the value matches. Take the time to remix and remix until it is right. Don’t settle for “close”, get the value exactly right. When you have a match, take a blank sheet of paper and record it with a little patch of paint. Then, move to the next value. See how many different values you find in your photo at the end. Here is a picture of the results of this exercise when I did it this morning.

Here is the startup—with my printout and bit a clean paper to record values.

Here is about midway.

And, here is the printout when it is covered. Keep in mind, this is not the same as making a painting. It is not even a value study. It is simply a piece of paper covered in paint—the benefit is in the process—not the product.

If you do this exercise until you have covered to whole photograph—I am convinced you will have learned something. You may not feel it, or be able to talk about it—but your eyes will be learning when you are doing this exercise. Try doing it everyday for a week for 30 minutes—and you will see an improvement in your work—I promise.

Okay, that is it for now. In my next post, I will teach you how to take this exercise a bit further into a formal study—or even into a painting. But, the process I described is a good exercise in and of itself—and worth doing even it you plan to throw away the finished product. The process will subconsciously teach your eyes to see values in a way you can never learn from a book or from looking at paintings. I am convinced, "learning to see" requires a physical/active engagement--there is no other way.

So, that is what I learned over the holidays, how about you?

All the best, sixtyminutearist.

"Monument (Merrick Butte)", Oil on Panel, 8x8 inches

"Monument (Merrick Butte)", Oil on Panel, 8x8 inches